Bayesian Statistics in Python#

In this chapter we will introduce how to basic Bayesian computations using Python.

Applying Bayes’ theorem: A simple example#

TBD: MOVE TO MULTIPLE TESTING EXAMPLE SO WE CAN USE BINOMIAL LIKELIHOOD

A person has a cough and flu-like symptoms, and gets a PCR test for COVID-19, which comes back postiive. What is the likelihood that they actually have COVID-19, as opposed to a regular cold or flu? We can use Bayes’ theorem to compute this. Let’s say that the local rate of symptomatic individuals who actually are infected with COVID-19 is 7.4% (as reported on July 10, 2020 for San Francisco); thus, our prior probability that someone with symptoms actually has COVID-19 is .074. The RT-PCR test used to identify COVID-19 RNA is highly specific (that is, it very rarelly reports the presence of the virus when it is not present); for our example, we will say that the specificity is 99%. Its sensitivity is not known, but probably is no higher than 90%.

First let’s look at the probability of disease given a single positive test.

sensitivity = 0.90

specificity = 0.99

prior = 0.074

likelihood = sensitivity # p(test|disease present)

marginal_likelihood = sensitivity * prior + (1 - specificity) * (1 - prior)

posterior = (likelihood * prior) / marginal_likelihood

posterior

0.8779330345373055

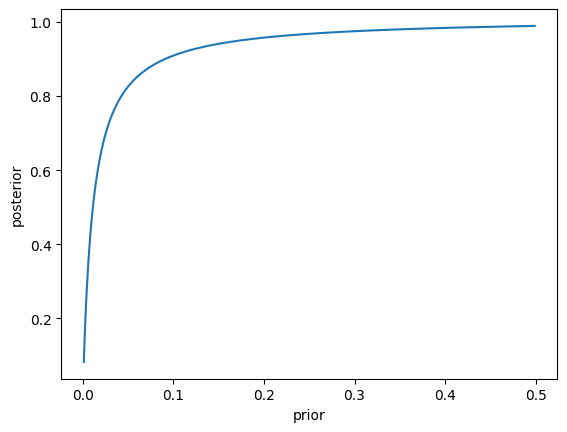

The high specificity of the test, along with the relatively high base rate of the disease, means that most people who test positive actually have the disease. Now let’s plot the posterior as a function of the prior. Let’s first create a function to compute the posterior, and then apply this with a range of values for the prior.

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import scipy.stats

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def compute_posterior(prior, sensitivity, specificity):

likelihood = sensitivity # p(test|disease present)

marginal_likelihood = sensitivity * prior + (1 - specificity) * (1 - prior)

posterior = (likelihood * prior) / marginal_likelihood

return(posterior)

prior_values = np.arange(0.001, 0.5, 0.001)

posterior_values = compute_posterior(prior_values, sensitivity, specificity)

plt.plot(prior_values, posterior_values)

plt.xlabel('prior')

_ = plt.ylabel('posterior')

This figure highlights a very important general point about diagnostic testing: Even when the test has high specificity, if a condition is rare then most positive test results will be false positives.

Estimating posterior distributions#

In this example we will look at how to estimate entire posterior distributions.

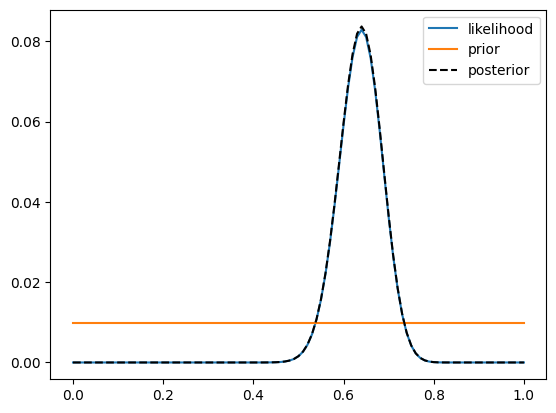

We will implement the drug testing example from the book. In that example, we administered a drug to 100 people, and found that 64 of them responded positively to the drug. What we want to estimate is the probability distribution for the proportion of responders, given the data. For simplicity we started with a uniform prior; that is, all proprtions of responding are equally likely to begin with. In addition, we will use a discrete probability distribution; that is, we will estimate the posterior probabiilty for each particular proportion of responders, in steps of 0.01. This greatly simplifies the math and still retains the main idea.

#+

num_responders = 64

num_tested = 100

bayes_df = pd.DataFrame({'proportion': np.arange(0.0, 1.01, 0.01)})

# compute the binomial likelihood of the observed data for each

# possible value of proportion

bayes_df['likelihood'] = scipy.stats.binom.pmf(num_responders,

num_tested,

bayes_df['proportion'])

# The prior is equal for all possible values

bayes_df['prior'] = 1 / bayes_df.shape[0]

# compute the marginal likelihood by adding up the likelihood of each possible proportion times its prior probability.

marginal_likelihood = (bayes_df['likelihood'] * bayes_df['prior']).sum()

bayes_df['posterior'] = (bayes_df['likelihood'] * bayes_df['prior']) / marginal_likelihood

# plot the likelihood, prior, and posterior

plt.plot(bayes_df['proportion'], bayes_df['likelihood'], label='likelihood')

plt.plot(bayes_df['proportion'], bayes_df['prior'], label='prior')

plt.plot(bayes_df['proportion'], bayes_df['posterior'],

'k--', label='posterior')

plt.legend()

#-

<matplotlib.legend.Legend at 0x7fe21c043e60>

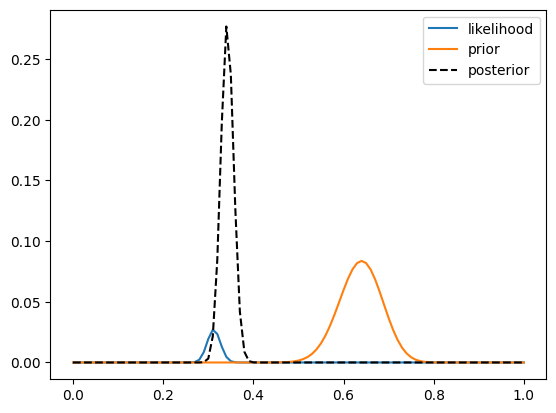

The plot shows that the posterior and likelihood are virtually identical, which is due to the fact that the prior is uniform across all possible values. Now let’s look at a case where the prior is not uniform. Let’s say that we now run a larger study of 1000 people with the same treatment, and we find that 312 of the 1000 individuals respond to the treatment. In this case, we can use the posterior from the earlier study of 100 people as the prior for our new study. This is what we sometimes refer to as Bayesian updating.

#+

num_responders = 312

num_tested = 1000

# copy the posterior from the previous analysis and rename it as the prior

study2_df = bayes_df[['proportion', 'posterior']].rename(columns={'posterior': 'prior'})

# compute the binomial likelihood of the observed data for each

# possible value of proportion

study2_df['likelihood'] = scipy.stats.binom.pmf(num_responders,

num_tested,

study2_df['proportion'])

# compute the marginal likelihood by adding up the likelihood of each possible proportion times its prior probability.

marginal_likelihood = (study2_df['likelihood'] * study2_df['prior']).sum()

study2_df['posterior'] = (study2_df['likelihood'] * study2_df['prior']) / marginal_likelihood

# plot the likelihood, prior, and posterior

plt.plot(study2_df['proportion'], study2_df['likelihood'], label='likelihood')

plt.plot(study2_df['proportion'], study2_df['prior'], label='prior')

plt.plot(study2_df['proportion'], study2_df['posterior'],

'k--', label='posterior')

plt.legend()

#-

<matplotlib.legend.Legend at 0x7fe21c110c50>

Here we see two important things. First, we see that the prior is substantially wider than the likelihood, which occurs because there is much more data going into the likelihood (1000 data points) compared to the prior (100 data points), and more data reduces our uncertainty. Second, we see that the posterior is much closer to the value observed for the second study than for the first, which occurs for the same reason — we put greater weight on the estimate that is more precise due to a larger sample.

Bayes factors#

There are no convenient off-the-shelf tools for estimating Bayes factors using Python, so we will use the rpy2 package to access the BayesFactor library in R. Let’s compute a Bayes factor for a T-test comparing the amount of reported alcohol computing between smokers versus non-smokers. First, let’s set up the NHANES data and collect a sample of 150 smokers and 150 nonsmokers.

#+

from nhanes.load import load_NHANES_data

nhanes_data = load_NHANES_data()

adult_nhanes_data = nhanes_data.query('AgeInYearsAtScreening > 17')

rseed = 1

# clean up smoking variables

adult_nhanes_data.loc[adult_nhanes_data['SmokedAtLeast100CigarettesInLife'] == 0, 'DoYouNowSmokeCigarettes'] = 'Not at all'

adult_nhanes_data.loc[:, 'SmokeNow'] = adult_nhanes_data['DoYouNowSmokeCigarettes'] != 'Not at all'

# Create average alcohol consumption variable between the two dietary recalls

adult_nhanes_data.loc[:, 'AvgAlcohol'] = adult_nhanes_data[['AlcoholGm_DR1TOT', 'AlcoholGm_DR2TOT']].mean(1)

adult_nhanes_data = adult_nhanes_data.dropna(subset=['AvgAlcohol'])

sample_size_per_group = 150

nonsmoker_sample = adult_nhanes_data.query('SmokeNow == False').sample(sample_size_per_group, random_state=rseed)[['SmokeNow', 'AvgAlcohol']]

smoker_sample = adult_nhanes_data.query('SmokeNow == True').sample(sample_size_per_group, random_state=rseed)[['SmokeNow', 'AvgAlcohol']]

full_sample = pd.concat((nonsmoker_sample, smoker_sample))

full_sample.loc[:, 'SmokeNow'] = full_sample['SmokeNow'].astype('int')

full_sample.groupby('SmokeNow').mean()

#-

/tmp/ipykernel_392/61854950.py:9: SettingWithCopyWarning:

A value is trying to be set on a copy of a slice from a DataFrame.

Try using .loc[row_indexer,col_indexer] = value instead

See the caveats in the documentation: https://pandas.pydata.org/pandas-docs/stable/user_guide/indexing.html#returning-a-view-versus-a-copy

adult_nhanes_data.loc[:, 'SmokeNow'] = adult_nhanes_data['DoYouNowSmokeCigarettes'] != 'Not at all'

/tmp/ipykernel_392/61854950.py:12: SettingWithCopyWarning:

A value is trying to be set on a copy of a slice from a DataFrame.

Try using .loc[row_indexer,col_indexer] = value instead

See the caveats in the documentation: https://pandas.pydata.org/pandas-docs/stable/user_guide/indexing.html#returning-a-view-versus-a-copy

adult_nhanes_data.loc[:, 'AvgAlcohol'] = adult_nhanes_data[['AlcoholGm_DR1TOT', 'AlcoholGm_DR2TOT']].mean(1)

| AvgAlcohol | |

|---|---|

| SmokeNow | |

| 0 | 5.748000 |

| 1 | 11.875333 |

Now let’s use functions from R to perform a standard t-test as well as compute a Bayes Factor for this comparison.

#+

# import the necessary functions from rpy2

import rpy2.robjects as robjects

from rpy2.robjects import r, pandas2ri

from rpy2.robjects.packages import importr

pandas2ri.activate()

# import the BayesFactor package

BayesFactor = importr('BayesFactor')

# import the data frames into the R workspace

robjects.globalenv["smoker_sample"] = smoker_sample

robjects.globalenv["nonsmoker_sample"] = nonsmoker_sample

# perform the standard t-test

ttest_output = r('print(t.test(smoker_sample$AvgAlcohol, nonsmoker_sample$AvgAlcohol, alternative="greater"))')

# compute the Bayes factor

r('bf = ttestBF(y=nonsmoker_sample$AvgAlcohol, x=smoker_sample$AvgAlcohol, nullInterval = c(0, Inf))')

r('print(bf[1]/bf[2])')

#-

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ModuleNotFoundError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[6], line 4

1 #+

2

3 # import the necessary functions from rpy2

----> 4 import rpy2.robjects as robjects

5 from rpy2.robjects import r, pandas2ri

6 from rpy2.robjects.packages import importr

ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'rpy2'

This shows that the difference between these groups is significant, and the Bayes factor suggests fairly strong evidence for a difference.