Chapter 10 Quantifying effects and designing studies

In the previous chapter we discussed how we can use data to test hypotheses. Those methods provided a binary answer: we either reject or fail to reject the null hypothesis. However, this kind of decision overlooks a couple of important questions. First, we would like to know how much uncertainty we have about the answer (regardless of which way it goes). In addition, sometimes we don’t have a clear null hypothesis, so we would like to see what range of estimates are consistent with the data. Second, we would like to know how large the effect actually is, since as we saw in the weight loss example in the previous chapter, a statistically significant effect is not necessarily a practically important effect.

In this chapter we will discuss methods to address these two questions: confidence intervals to provide a measure of our uncertainty about our estimates, and effect sizes to provide a standardized way to understand how large the effects are. We will also discuss the concept of statistical power which tells us how likely we are to find any true effects that actually exist.

10.1 Confidence intervals

So far in the book we have focused on estimating a single value statistic. For example, let’s say we want to estimate the mean weight of adults in the NHANES dataset, so we take a sample from the dataset and estimate the mean. In this sample, the mean weight was 79.92 kilograms. We refer to this as a point estimate since it provides us with a single number to describe our estimate of the population parameter. However, we know from our earlier discussion of sampling error that there is some uncertainty about this estimate, which is described by the standard error. You should also remember that the standard error is determined by two components: the population standard deviation (which is the numerator), and the square root of the sample size (which is in the denominator). The population standard deviation is a generally unknown but fixed parameter that is not under our control, whereas the sample size is under our control. Thus, we can decrease our uncertainty about the estimate by increasing our sample size – up to the limit of the entire population size, at which point there is no uncertainty at all because we can just calculate the population parameter directly from the data of the entire population.

We would often like to have a way to more directly describe our uncertainty about a statistical estimate, which we can accomplish using a confidence interval. Most people are familiar with confidence intervals through the idea of a “margin of error” for political polls. These polls usually try to provide an answer that is accurate within +/- 3 percent. For example, when a candidate is estimated to win an election by 9 percentage points with a margin of error of 3, the percentage by which they will win is estimated to fall within 6-12 percentage points. In statistics we refer to this kind of range of values as a confidence interval, which provides a range of values for our parameter estimate that are consistent with our sample data, rather than just giving us a single estimate based on the data. The wider the confidence interval, the more uncertain we are about our parameter estimate.

Confidence intervals are notoriously confusing, primarily because they don’t mean what we might intuitively think they mean. If I tell you that I have computed a “95% confidence interval” for my statistic, then it would seem natural to think that we can have 95% confidence that the true parameter value falls within this interval. However, as we will see throughout the course, concepts in statistics often don’t mean what we think they should mean. In the case of confidence intervals, we can’t interpret them in this way because the population parameter has a fixed value – it either is or isn’t in the interval, so it doesn’t make sense to talk about the probability of that occurring. Jerzy Neyman, the inventor of the confidence interval, said:

“The parameter is an unknown constant and no probability statement concerning its value may be made.”(J. Neyman 1937)

Instead, we have to view the confidence interval procedure from the same standpoint that we viewed hypothesis testing: As a procedure that in the long run will allow us to make correct statements with a particular probability. Thus, the proper interpretation of the 95% confidence interval is that it is an interval that will contain the true population mean 95% of the time, and in fact we can confirm that using simulation, as you will see below.

The confidence interval for the mean is computed as:

\[ CI = \text{point estimate} \pm \text{critical value} * \text{standard error} \]

where the critical value is determined by the sampling distribution of the estimate. The important question, then, is how we obtain our estimate for that sampling distribution.

10.1.1 Confidence intervals using the normal distribution

If we know the population standard deviation, then we can use the normal distribution to compute a confidence interval. We usually don’t, but for our example of the NHANES dataset we do, since we are treating the entire dataset as the population (it’s 21.3 for weight).

Let’s say that we want to compute a 95% confidence interval for the mean. The critical value would then be the values of the standard normal distribution that capture 95% of the distribution; these are simply the 2.5th percentile and the 97.5th percentile of the distribution, which we can compute using our statistical software, and come out to \(\pm 1.96\). Thus, the confidence interval for the mean (\(\bar{X}\)) is:

\[ CI = \bar{X} \pm 1.96*SE \]

Using the estimated mean from our sample (79.92) and the known population standard deviation, we can compute the confidence interval of [77.28,82.56].

10.1.2 Confidence intervals using the t distribution

As stated above, if we knew the population standard deviation, then we could use the normal distribution to compute our confidence intervals. However, in general we don’t – in which case the t distribution is more appropriate as a sampling distribution. Remember that the t distribution is slightly broader than the normal distribution, especially for smaller samples, which means that the confidence intervals will be slightly wider than they would if we were using the normal distribution. This incorporates the extra uncertainty that arises when we estimate parameters based on small samples.

We can compute the 95% confidence interval in a way similar to the normal distribution example above, but the critical value is determined by the 2.5th percentile and the 97.5th percentile of the t distribution with the appropriate degrees of freedom. Thus, the confidence interval for the mean (\(\bar{X}\)) is:

\[ CI = \bar{X} \pm t_{crit}*SE \]

where \(t_{crit}\) is the critical t value. For the NHANES weight example (with sample size of 250), the confidence interval would be 79.92 +/- 1.97 * 1.41 [77.15 - 82.69].

Remember that this doesn’t tell us anything about the probability of the true population value falling within this interval, since it is a fixed parameter (which we know is 81.77 because we have the entire population in this case) and it either does or does not fall within this specific interval (in this case, it does). Instead, it tells us that in the long run, if we compute the confidence interval using this procedure, 95% of the time that confidence interval will capture the true population parameter.

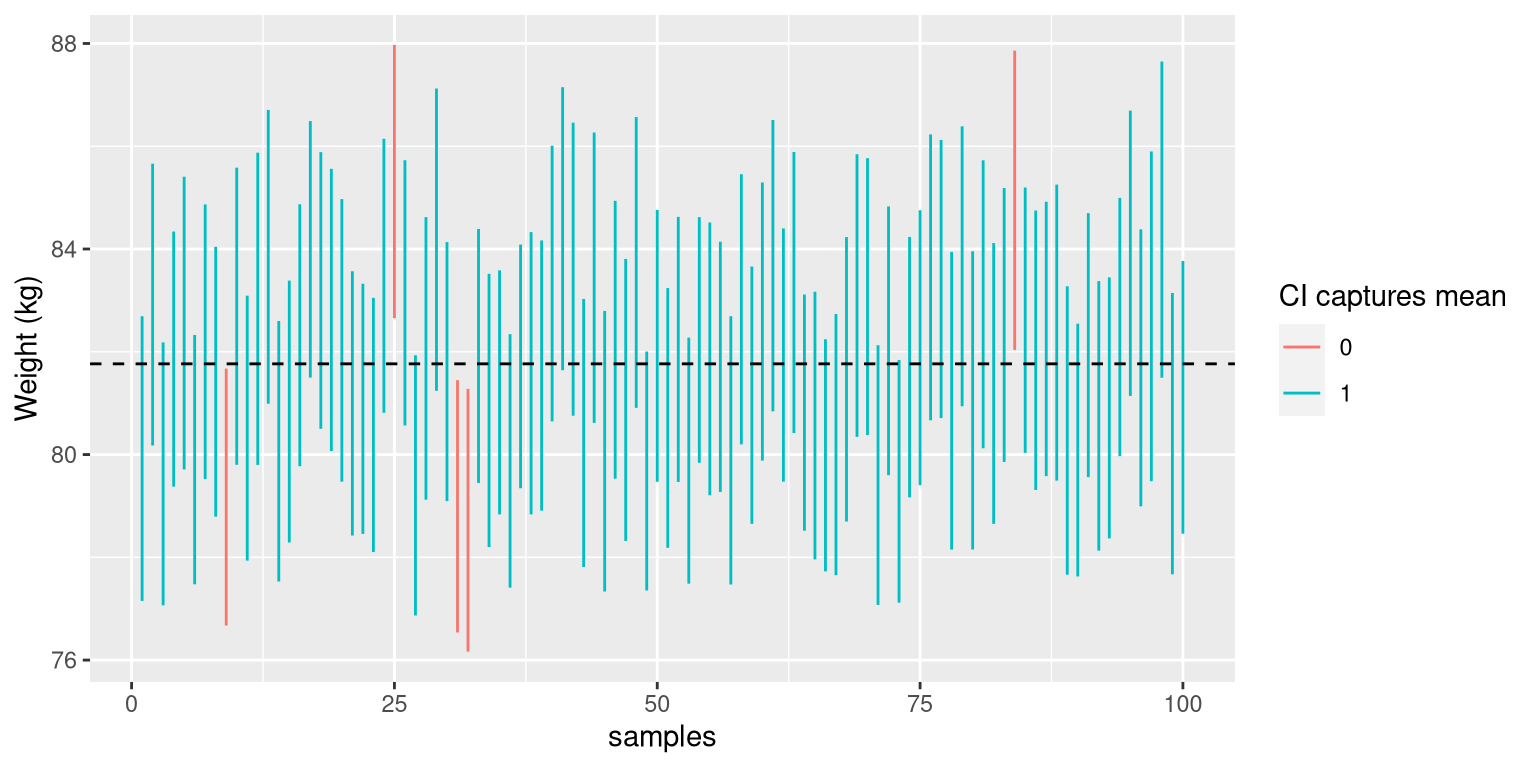

We can see this using the NHANES data as our population; in this case, we know the true value of the population parameter, so we can see how often the confidence interval ends up capturing that value across many different samples. Figure 10.1 shows the confidence intervals for estimated mean weight computed for 100 samples from the NHANES dataset. Of these, 95 captured the true population mean weight, showing that the confidence interval procedure performs as it should.

Figure 10.1: Samples were repeatedly taken from the NHANES dataset, and the 95% confidence interval of the mean was computed for each sample. Intervals shown in red did not capture the true population mean (shown as the dotted line).

10.1.3 Confidence intervals and sample size

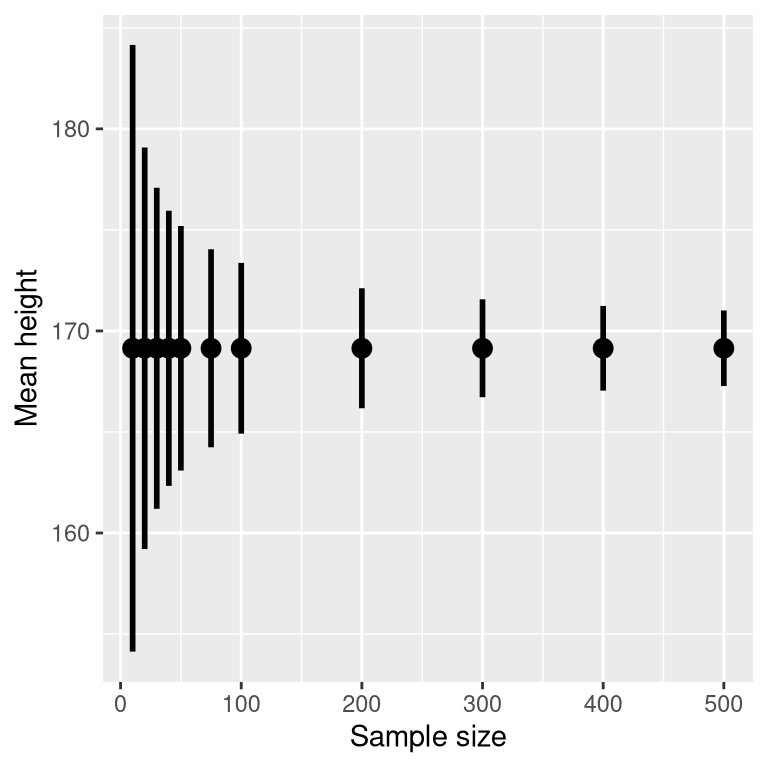

Because the standard error decreases with sample size, the confidence interval should get narrower as the sample size increases, providing progressively tighter bounds on our estimate. Figure 10.2 shows an example of how the confidence interval would change as a function of sample size for the weight example. From the figure it’s evident that the confidence interval becomes increasingly tighter as the sample size increases, but increasing samples provide diminishing returns, consistent with the fact that the denominator of the confidence interval term is proportional to the square root of the sample size.

Figure 10.2: An example of the effect of sample size on the width of the confidence interval for the mean.

10.1.4 Computing confidence intervals using the bootstrap

In some cases we can’t assume normality, or we don’t know the sampling distribution of the statistic. In these cases, we can use the bootstrap (which we introduced in Chapter 8). As a reminder, the bootstrap involves repeatedly resampling the data with replacement, and then using the distribution of the statistic computed on those samples as a surrogate for the sampling distribution of the statistic.These are the results when we use the built-in bootstrapping function in R to compute the confidence interval for weight in our NHANES sample:

## BOOTSTRAP CONFIDENCE INTERVAL CALCULATIONS

## Based on 1000 bootstrap replicates

##

## CALL :

## boot.ci(boot.out = bs, type = "perc")

##

## Intervals :

## Level Percentile

## 95% (78, 84 )

## Calculations and Intervals on Original ScaleThese values are fairly close to the values obtained using the t distribution above, though not exactly the same.

10.1.5 Relation of confidence intervals to hypothesis tests

There is a close relationship between confidence intervals and hypothesis tests. In particular, if the confidence interval does not include the null hypothesis, then the associated statistical test would be statistically significant. For example, if you are testing whether the mean of a sample is greater than zero with \(\alpha = 0.05\), you could simply check to see whether zero is contained within the 95% confidence interval for the mean.

Things get trickier if we want to compare the means of two conditions (Schenker and Gentleman 2001). There are a couple of situations that are clear. First, if each mean is contained within the confidence interval for the other mean, then there is definitely no significant difference at the chosen confidence level. Second, if there is no overlap between the confidence intervals, then there is certainly a significant difference at the chosen level; in fact, this test is substantially conservative, such that the actual error rate will be lower than the chosen level. But what about the case where the confidence intervals overlap one another but don’t contain the means for the other group? In this case the answer depends on the relative variability of the two variables, and there is no general answer. However, one should in general avoid using the “eyeball test” for overlapping confidence intervals.

10.2 Effect sizes

“Statistical significance is the least interesting thing about the results. You should describe the results in terms of measures of magnitude – not just, does a treatment affect people, but how much does it affect them.” Gene Glass, quoted in (Sullivan and Feinn 2012)

In the previous chapter, we discussed the idea that statistical significance may not necessarily reflect practical significance. In order to discuss practical significance, we need a standard way to describe the size of an effect in terms of the actual data, which we refer to as an effect size. In this section we will introduce the concept and discuss various ways that effect sizes can be calculated.

An effect size is a standardized measurement that compares the size of some statistical effect to a reference quantity, such as the variability of the statistic. In some fields of science and engineering, this idea is referred to as a “signal to noise ratio”. There are many different ways that the effect size can be quantified, which depend on the nature of the data.

10.2.1 Cohen’s D

One of the most common measures of effect size is known as Cohen’s d, named after the statistician Jacob Cohen (who is most famous for his 1994 paper titled “The Earth Is Round (p < .05)”). It is used to quantify the difference between two means, in terms of their standard deviation:

\[ d = \frac{\bar{X}_1 - \bar{X}_2}{s} \]

where \(\bar{X}_1\) and \(\bar{X}_2\) are the means of the two groups, and \(s\) is the pooled standard deviation (which is a combination of the standard deviations for the two samples, weighted by their sample sizes):

\[ s = \sqrt{\frac{(n_1 - 1)s^2_1 + (n_2 - 1)s^2_2 }{n_1 +n_2 -2}} \] where \(n_1\) and \(n_2\) are the sample sizes and \(s^2_1\) and \(s^2_2\) are the standard deviations for the two groups respectively. Note that this is very similar in spirit to the t statistic — the main difference is that the denominator in the t statistic is based on the standard error of the mean, whereas the denominator in Cohen’s D is based on the standard deviation of the data. This means that while the t statistic will grow as the sample size gets larger, the value of Cohen’s D will remain the same.

| D | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| 0.0 - 0.2 | neglibible |

| 0.2 - 0.5 | small |

| 0.5 - 0.8 | medium |

| 0.8 - | large |

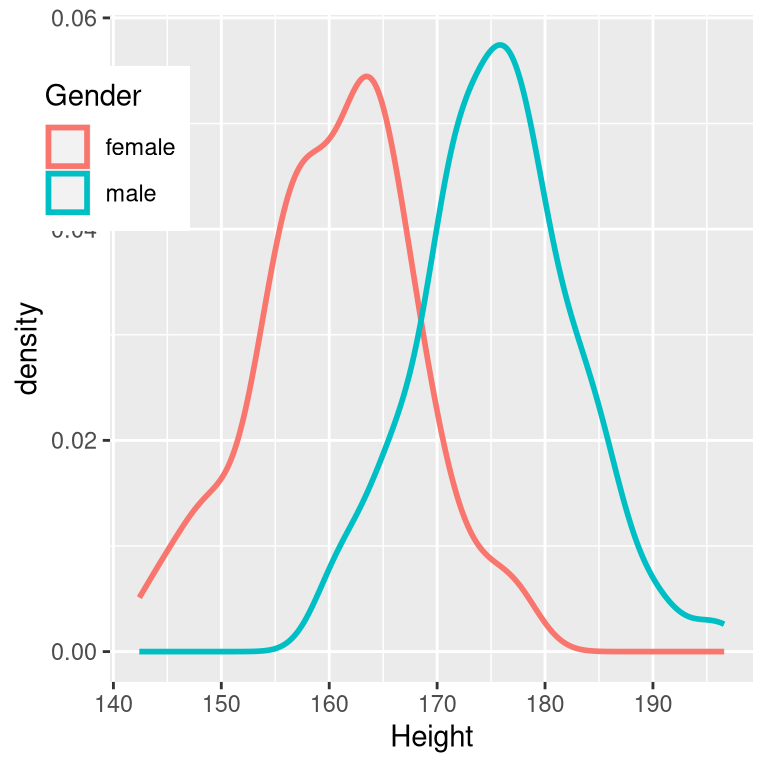

There is a commonly used scale for interpreting the size of an effect in terms of Cohen’s d, shown in Table 10.1. It can be useful to look at some commonly understood effects to help understand these interpretations. For example, the effect size for gender differences in adult height (d = 2.05) is very large by reference to our table above. We can also see this by looking at the distributions of male and female heights in a sample from the NHANES dataset. Figure 10.3 shows that the two distributions are quite well separated, though still overlapping, highlighting the fact that even when there is a very large effect size for the difference between two groups, there will be individuals from each group that are more like the other group.

Figure 10.3: Smoothed histogram plots for male and female heights in the NHANES dataset, showing clearly distinct but also clearly overlapping distributions.

It is also worth noting that we rarely encounter effects of this magnitude in science, in part because they are such obvious effects that we don’t need scientific research to find them. As we will see in Chapter 18 on reproducibility, very large reported effects in scientific research often reflect the use of questionable research practices rather than truly huge effects in nature. It is also worth noting that even for such a huge effect, the two distributions still overlap - there will be some females who are taller than the average male, and vice versa. For most interesting scientific effects, the degree of overlap will be much greater, so we shouldn’t immediately jump to strong conclusions about individuals from different populations based on even a large effect size.

10.2.2 Pearson’s r

Pearson’s r, also known as the correlation coefficient, is a measure of the strength of the linear relationship between two continuous variables. We will discuss correlation in much more detail in Chapter 13, so we will save the details for that chapter; here, we simply introduce r as a way to quantify the relation between two variables.

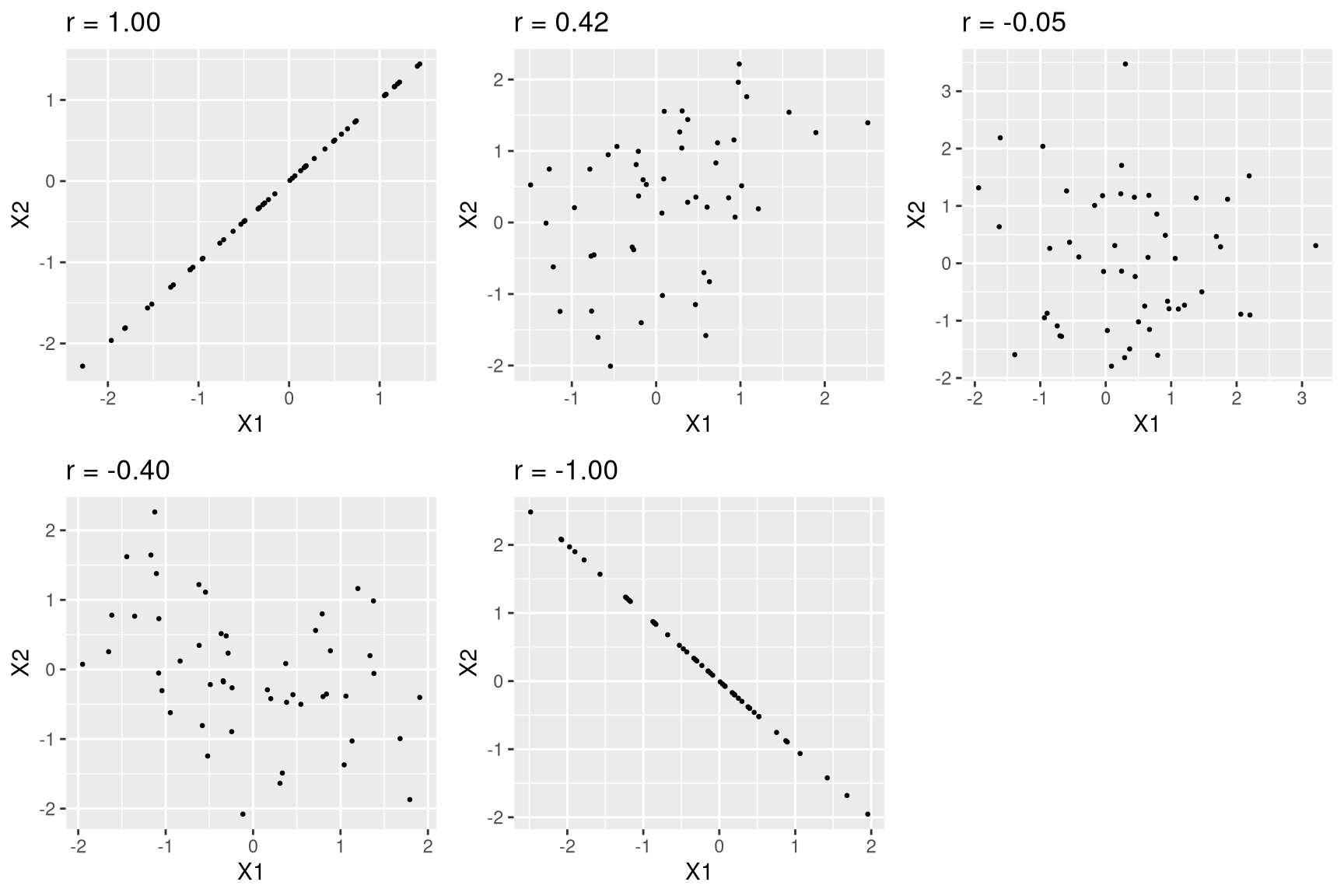

r is a measure that varies from -1 to 1, where a value of 1 represents a perfect positive relationship between the variables, 0 represents no relationship, and -1 represents a perfect negative relationship. Figure 10.4 shows examples of various levels of correlation using randomly generated data.

Figure 10.4: Examples of various levels of Pearson’s r.

10.2.3 Odds ratio

In our earlier discussion of probability we discussed the concept of odds – that is, the relative likelihood of some event happening versus not happening:

\[ odds\ of\ A = \frac{P(A)}{P(\neg A)} \]

We also discussed the odds ratio, which is simply the ratio of two odds. The odds ratio is a useful way to describe effect sizes for binary variables.

For example, let’s take the case of smoking and lung cancer. A study published in the International Journal of Cancer in 2012 (Pesch et al. 2012) combined data regarding the occurrence of lung cancer in smokers and individuals who have never smoked across a number of different studies. Note that these data come from case-control studies, which means that participants in the studies were recruited because they either did or did not have cancer; their smoking status was then examined. These numbers (shown in Table 10.2) thus do not represent the prevalence of cancer amongst smokers in the general population – but they can tell us about the relationship between cancer and smoking.

| Status | NeverSmoked | CurrentSmoker |

|---|---|---|

| No Cancer | 2883 | 3829 |

| Cancer | 220 | 6784 |

We can convert these numbers to odds ratios for each of the groups. The odds of a non-smoker having lung cancer are 0.08 whereas the odds of a current smoker having lung cancer are 1.77. The ratio of these odds tells us about the relative likelihood of cancer between the two groups: The odds ratio of 23.22 tells us that the odds of lung cancer in smokers are roughly 23 times higher than never-smokers.

10.3 Statistical power

Remember from the previous chapter that under the Neyman-Pearson hypothesis testing approach, we have to specify our level of tolerance for two kinds of errors: False positives (which they called Type I error) and false negatives (which they called Type II error). People often focus heavily on Type I error, because making a false positive claim is generally viewed as a very bad thing; for example, the now discredited claims by Wakefield (1999) that autism was associated with vaccination led to anti-vaccine sentiment that has resulted in substantial increases in childhood diseases such as measles. Similarly, we don’t want to claim that a drug cures a disease if it really doesn’t. That’s why the tolerance for Type I errors is generally set fairly low, usually at \(\alpha = 0.05\). But what about Type II errors?

The concept of statistical power is the complement of Type II error – that is, it is the likelihood of finding a positive result given that it exists:

\[ power = 1 - \beta \]

Another important aspect of the Neyman-Pearson model that we didn’t discuss earlier is the fact that in addition to specifying the acceptable levels of Type I and Type II errors, we also have to describe a specific alternative hypothesis – that is, what is the size of the effect that we wish to detect? Otherwise, we can’t interpret \(\beta\) – the likelihood of finding a large effect is always going to be higher than finding a small effect, so \(\beta\) will differ depending on the size of effect we are trying to detect.

There are three factors that can affect statistical power:

- Sample size: Larger samples provide greater statistical power

- Effect size: A given design will always have greater power to find a large effect than a small effect (because finding large effects is easier)

- Type I error rate: There is a relationship between Type I error and power such that (all else being equal) decreasing Type I error will also decrease power.

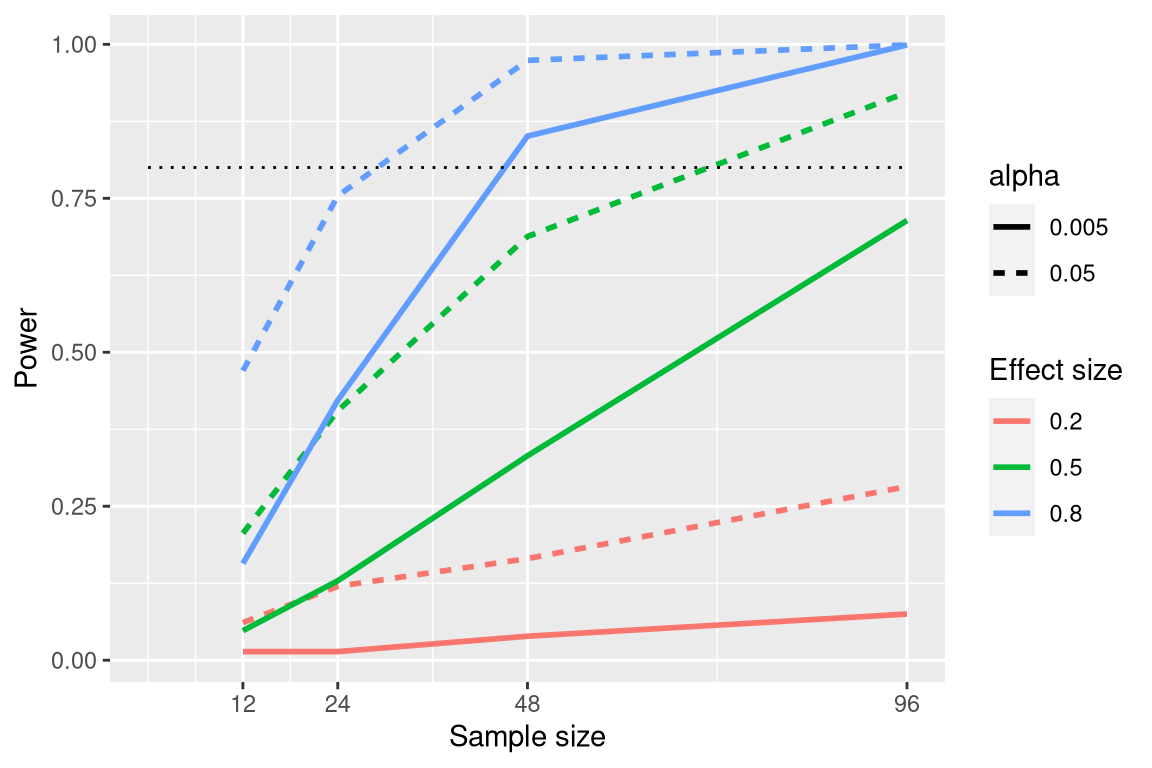

We can see this through simulation. First let’s simulate a single experiment, in which we compare the means of two groups using a standard t-test. We will vary the size of the effect (specified in terms of Cohen’s d), the Type I error rate, and the sample size, and for each of these we will examine how the proportion of significant results (i.e. power) is affected. Figure 10.5 shows an example of how power changes as a function of these factors.

Figure 10.5: Results from power simulation, showing power as a function of sample size, with effect sizes shown as different colors, and alpha shown as line type. The standard criterion of 80 percent power is shown by the dotted black line.

This simulation shows us that even with a sample size of 96, we will have relatively little power to find a small effect (\(d = 0.2\)) with \(\alpha = 0.005\). This means that a study designed to do this would be futile – that is, it is almost guaranteed to find nothing even if a true effect of that size exists.

There are at least two important reasons to care about statistical power. First, if you are a researcher, you probably don’t want to spend your time doing futile experiments. Running an underpowered study is essentially futile, because it means that there is a very low likelihood that one will find an effect, even if it exists. Second, it turns out that any positive findings that come from an underpowered study are more likely to be false compared to a well-powered study, a point we discuss in more detail in Chapter 18.

10.3.1 Power analysis

Fortunately, there are tools available that allow us to determine the statistical power of an experiment. The most common use of these tools is in planning an experiment, when we would like to determine how large our sample needs to be in order to have sufficient power to find our effect of interest.

Let’s say that we are interested in running a study of how a particular personality trait differs between users of iOS versus Android devices. Our plan is collect two groups of individuals and measure them on the personality trait, and then compare the two groups using a t-test. In this case, we would think that a medium effect (\(d = 0.5\)) is of scientific interest, so we will use that level for our power analysis. In order to determine the necessary sample size, we can use power function from our statistical software:

##

## Two-sample t test power calculation

##

## n = 64

## delta = 0.5

## sd = 1

## sig.level = 0.05

## power = 0.8

## alternative = two.sided

##

## NOTE: n is number in *each* groupThis tells us that we would need at least 64 subjects in each group in order to have sufficient power to find a medium-sized effect. It’s always important to run a power analysis before one starts a new study, to make sure that the study won’t be futile due to a sample that is too small.

It might have occurred to you that if the effect size is large enough, then the necessary sample will be very small. For example, if we run the same power analysis with an effect size of d=2, then we will see that we only need about 5 subjects in each group to have sufficient power to find the difference.

##

## Two-sample t test power calculation

##

## n = 5.1

## d = 2

## sig.level = 0.05

## power = 0.8

## alternative = two.sided

##

## NOTE: n is number in *each* groupHowever, it’s rare in science to be doing an experiment where we expect to find such a large effect – just as we don’t need statistics to tell us that 16-year-olds are taller than than 6-year-olds. When we run a power analysis, we need to specify an effect size that is plausible and/or scientifically interesting for our study, which would usually come from previous research. However, in Chapter 18 we will discuss a phenomenon known as the “winner’s curse” that likely results in published effect sizes being larger than the true effect size, so this should also be kept in mind.

10.4 Learning objectives

Having read this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe the proper interpretation of a confidence interval, and compute a confidence interval for the mean of a given dataset.

- Define the concept of effect size, and compute the effect size for a given test.

- Describe the concept of statistical power and why it is important for research.